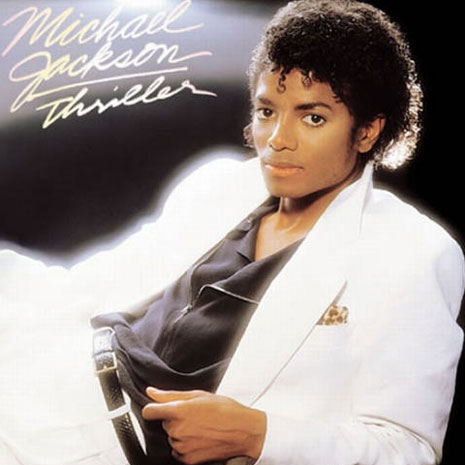

Thriller de Michael Jackson la reseña

Jun 26, 2009 Author: Rodrigo O. | Filed under: Musica InglesDesde que en los tres primeros años el primer álbum solista de Michael Jackson, Off the Wall, vendió 7 millones de copias y colocó cuatro hits, la música negra viró al estilo bailable pero ultraestilizado cuyo epítome es Off the Wall. Desde Prince a Marvin Gave, del rap a Rick James, los artistas negros han incorporado cada vez más temas maduros y aventurados -cultura, sexo, política- en su música arenosa y valiente. Así que cuando el primer single solista de Jackson desde 1979 resultó ser la endeble balada MOR con el estribillo “The doggone girl is mine” [“La chica condenada es mía”], cantada con un Paul McCartney domesticado, parecía que había perdido el tren.

Pero la superficialidad de ese hit terriblemente pegadizo contradice la sustancia sorprendente de Thriller. Más que recalentar el funk despreocupado y agradable de Off the Wall, Jackson ha cocinado un sabroso LP cuyos ritmos rápidos no oscurecen sus mensajes escalofriantes y oscuros. Especialmente en las composiciones del propio Jackson, el sonido casi obsesivo y tenso de Thriller complementa una letra que delinea un mundo que ha puesto al chico de 24 años a la defensiva. “They´re out to get you, better leave while you can / Don´t wanna be a boy, you wanna be a man” [“Están tratando de agarrarte, y mejor andate mientras puedas / No querés ser un chico, querés ser un hombre”] . Ha sido una época desafiante para Jackson -sus padres se podrían separar, él estuvo implicado en un reclamo de paternidad- y ha respondido a esos desafíos de frente. Ha dejado atrás al infantil falsetto que salpicó sus hits desde from “I Want You Back” hasta “Don´t Stop ´Til You Get Enough” y eligió canalizar sus tormentos en una voz repleta y adulta, con una determinación entusiasta que es matizada por la tristeza. La nueva actitud de Jackson le da a Thriller un tono más profundo, sin la urgencia visceral y emocional de su trabajo previo, y marca otra línea divisoria de aguas en el desarrollo creador de este artista tremendamente talentoso.

Tomemos “Billie Jean”, un funk insistente cuyo mensaje no podía ser más embotado: “Ella dice que soy el único / pero el niño no es mi hijo”. El espíritu festivo que difundió Off the Wall lo terminó poniendo en problemas, y él templa esa euforia con la sospecha. “¿Qué querés decir con que soy el único?”, pregunta a su mujer fatal, “que bailará en el piso?” Es una canción casi dolorosamente triste, pero una frase que golpea subyace a sus sentimientos: “Billie Jean no es mi amante” es repetido incesantemente cuando la canción termina.

“Billie Jean” es mencionada al pasar en uno de los temas más combativos de Thriller, el hiperactivo “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’”, en donde Jackson habla también de la prensa, los chismes de toda clase y otros focos de problemas. Aquí las emociones son tan crudas que la canción casi se sale del control. “Alguien siempre está tratando de hacer llorar a mi bebé”, lamenta, y ese sentido de cuasi paranoia se acerca a la amargura en el estribillo: “Sos una verdura, sos una verdura / Ellos te comerán, sos una verdura”. Es un tema que es casi tan emocionante como ver cómo Jackson se motiva a través del escenario en un concierto -y mucho más imprevisible. Estas letras no le quitarán el sueño a Elvis Costello, pero muestran que Jackson ha progresado desde los sentimientos hey-vamos-a-coger que dominaban Off the Wall. La completa vitalidad del setting musical obvia cualquier sentido de autocompasión. La producción de Quincy Jones -Jackson coprodujo sus propias composiciones- es más excesiva que lo usual, y refrescantemente libre de sentimentalismos. Por otra parte, está trabajando con lo que quizás sea el instrumento más espectacular de la música pop: la voz de Michael Jackson. Donde artistas menores necesitan una sección de cuerda o la explosión lujuriosa de un sintetizador, Jackson sólo necesita cantar para transmitir la emoción profunda y sincera. Su habilidad cruda y su convicción hacen que temas como “Baby Be Mine” y “Wanna Be Startin´ Somethin´” sean cortes de primera, incluso el salvaje “The Girl Is Mine”. Bueno, casi.

Tal vez la mejor canción aquí sea “Beat It”, una declaración esto-no-es-disco, si tal cosa existe. La voz de Jackson planea por sobre la melodía, Eddie Van Halen interviene con un estupendo solo de guitarra, uno podría construir un centro de convenciones con el ritmo de base, y el resultado es una ingeniosa canción bailable. Programadores, tomen nota.

La mayor falla de Jackson ha sido su tendencia a la ostentación, y mientras en Thriller ha limitado su impulso, no lo ha aplacado del todo. El fin del lado dos, especialmente “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing)”, no está a la altura de los otros temas. Y la canción del título, que al principio suena como un examen metafórico de la misma manía persecutoria que marca los mejores momentos del LP, degenera en un camp tonto, con un rap de Vincent Price. (¿No podían conseguir al Conde Floyd?)

No es secreto que a Jackson le gusta el negocio del espectáculo y el glamour que acarrea. Su talento, no sólo cantando sino también bailando y actuando, podría convertirlo en un perfecto artista mainstream . Piénsenlo. La fuerte convicción de Thriller ofrece la esperanza de que Michael todavía está muy lejos de sucumbir a las trampas de Las Vegas. Puede que Thriller no sea el 1999 de Michael Jackson, pero es un gran y sonoro paso en la dirección correcta.

(RS 387)

Christopher Connelly

En ingles:

In the three years since Michael Jackson’s first solo album, Off the Wall, sold 7 million copies and spawned four hit singles, black music has veered away from the danceable but ultraslick style that Off the Wall epitomized. From Prince to Marvin Gave, from rap to Rick James, black artists have incorporated increasingly mature and adventurous themes — culture, sex, politics — into grittier, gutsier music. So when Jackson’s first solo single since 1979 turned out to be a wimpoid MOR ballad with the refrain “the doggone girl is mine,” sung with a tame Paul McCartney, it looked like the train had left the station without him.

But the superficiality of that damnably catchy hit belies the surprising substance of Thriller. Rather than reheating Off the Wall’s agreeably mindless funk, Jackson has cooked up a zesty LP whose uptempo workouts don’t obscure its harrowing, dark messages. Particularly on Jackson’s own compositions, Thriller’s tense, nearly obsessive sound complements lyrics that delineate a world that has put the twenty-four-year-old on the defensive. “They’re out to get you, better leave while you can / Don’t wanna be a boy, you wanna be a man.” It’s been a challenging time for Jackson — his parents may separate, he’s been involved in a paternity claim — and he’s responded to those challenges head-on. He’s dropped the boyish falsetto that sparked his hits from “I Want You Back” to “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” and chosen to address his tormentors in a full, adult voice with a feisty determination that is tinged by sadness. Jackson’s new attitude gives Thriller a deeper, if less visceral, emotional urgency than any of his previous work, and marks another watershed in the creative development of this prodigiously talented performer.

Take “Billie Jean,” a lean, insistent funk number whose message couldn’t be more blunt: “She says I am the one / But the kid is not my son.” The party spirit that suffused Off the Wall has landed him in trouble, and he tempers that exuberance with suspicion. “What do you mean I am the one,” he quizzically asks his femme fatale, “who will dance on the floor?” It’s a sad, almost mournful song, but a thumping resolve underlies his feelings: “Billie Jean is not my lover” is incessantly repeated as the song fades out.

Billie Jean is mentioned in passing in Thriller’s most combative track, the hyperactive “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” wherein Jackson also takes on the press, gossips of all kinds and other grief-givers. Here, the emotions are so raw that the song nearly goes out of control. “Somebody’s always tryin’ to start my baby crying,” he laments, and that sense of quasi paranoia yields to near-bitterness in the chorus: “You’re a vegetable, you’re a vegetable / They’ll eat off you, you’re a vegetable.” It’s a tune that’s almost as exciting as seeing Jackson motivate himself across a concert stage — and a lot more unpredictable. These lyrics won’t keep Elvis Costello awake nights, but they do show that Jackson has progressed past the hey-let’s-hustle sentiments that dominated Off the Wall.

The sheer vitality of the musical setting obviates any sense of self-pity. Quincy Jones’ production — Jackson coproduced his own compositions — is sparer than usual, and refreshingly free of schmaltz. Then again, he’s working with what might be pop music’s most spectacular instrument: Michael Jackson’s voice. Where lesser artists need a string section or a lusty blast from a synthesizer, Jackson need only sing to convey deep, heartfelt emotion. His raw ability and conviction make material like “Baby Be Mine” and “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin'” into first-class cuts and even salvage “The Girl Is Mine.” Well, almost.

Maybe the best song here is “Beat It,” a this-ain’t-no-disco AOR track if ever I heard one. Jackson’s voice soars all over the melody, Eddie Van Halen checks in with a blistering guitar solo, you could build a convention center on the backbeat, and the result is one nifty dance song. Programmers, take note.

Jackson’s greatest failing has been a tendency to go for the glitz, and while he’s curbed the urge on Thriller, he hasn’t obliterated it entirely. The end of side two, especially “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing),” isn’t up to the spunky character of the other tracks. And the title song, which at first sounds like a metaphoric examination of the same under-siege mentality that marks the LP’s best moments, instead degenerates into silly camp, with a rap by Vincent Price. (Couldn’t they get Count Floyd?)

Jackson has made no secret of his affection for traditional showbiz and the glamour that goes with it. His talents, not just singing but dancing and acting, could make him a perfect mainstream performer. Perish the thought. The fiery conviction of Thriller offers hope that Michael is still a long way away from succumbing to the lures of Vegas. Thriller may not be Michael Jackson’s 1999, but it’s a gorgeous, snappy step in the right direction. (RS 387)

Christopher Connelly

Tags: albums, michael jackson, reseñas

Deprecated: Function comments_rss_link is deprecated since version 2.5.0! Use post_comments_feed_link() instead. in /home/j7xay4ktlsv5/public_html/expectaculos.net/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6078

RSS feed for comments on this post

Buscador

Por Tema:

- blogs (740)

- Cultura (191)

- deportes (1,194)

- Farandula (3,351)

- humor (134)

- juegos (134)

- miniposts (43)

- Musica Español (953)

- Musica Ingles (2,479)

- nsfw (125)

- Oldies (61)

- otros (1,243)

- patrocinados (7)

- peliculas (2,140)

- politica (240)

- Press (25)

- quotes (98)

- radio (114)

- tech (702)

- television (2,910)

Recientes

- Nominaciones a los premios Emmy 2024

- Millie Bobby Brown devela su figura de cera en Londres

- La nueva sesion de fotos de Emily Ratajkowski

- Cuarta portada de Childstar de Danna Paola

- La maldición de Hechizada

- Emma Watson cumple 34 años

- Danna Paola quiere apropiarse de cuenta de twitter

- Olivia Ponton para Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition 2023

- Cynthia Rodriguez embarazada en bikini

- Murió Rubén Moya, fue la voz de He-Man